Hypersonic Flight — The Greed For Speed

AVIATION'S QUEST TO RUN FIVE TIMES FASTER THAN SOUND

by Katrina Balmaceda Uy

WHEN AMERICAN PILOT CHUCK YEAGER BROKE THE SOUND BARRIER (MACH 1) IN 1947, HE DIDN’T FEEL A THING. “Grandma could be sitting up there sipping lemonade”, he later said of the relatively smooth flight. Not so for Major Robert White and his successful attempts to go hypersonic — or five times the speed of sound, at Mach 5. “The airplane got so damned hot that it popped and banged like an old iron stove. It spewed smoke out of its bowels and it twitched like frog legs in a skillet”, wrote White.

This was in the early 1960s. And while rockets, experimental aircraft, and the Space Shuttle have long since surpassed Mach 5, engineers today have yet to find a way to make it safe, comfortable, and efficient for humans to fly that fast. The commercial appeal is obvious. At such speed, crossing the Pacific Ocean takes less than two hours. But flying at Mach 5 also exposes aircraft and humans to extreme conditions.

Before going hypersonic, a vehicle needs to reach an altitude of at least 60,000 feet, where the air is thin and atmospheric pressure is very low (a hypersonic vehicle below 60,000 feet will explode from pressure). The interiors need to be highly pressurised, as the lack of atmospheric pressure will cause exposed bodily fluids, such as saliva, to boil at the human body’s normal temperature.

DUE TO THE EXTREME HEAT, HYPERSONIC AIRCRAFT TYPICALLY USE SUPERSONIC COMBUSTION RAMJET OR ‘SCRAMJET’ ENGINES

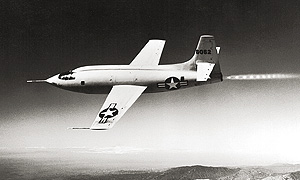

At Mach 5 and beyond, aircraft experience aerodynamic friction so intense that the heat it produces — somewhere in the range of 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit – can melt steel. When White flew NASA’s X-15 research aircraft beyond Mach 5 in the ’60s, its outer windshield layer cracked due to heat distortion and gravity pressures four times more than normal upon atmospheric re-entry.

Due to the extreme heat, hypersonic aircraft typically use supersonic-combustion ramjet or ‘scramjet’ engines, which forcefully compress air from the atmosphere to cause combustion. Such engines are not made to move from a standstill, and require take-off assistance, usually from a rocket or an aircraft launcher. Most hypersonic aircraft, then, are designed to rely more on lift than on wings

This is why most hypersonic vehicles have been tested unmanned. In November 2004, NASA’s X-43A unmanned experimental aircraft reached a speed of at least Mach 9.2. Primarily fuelled by hydrogen, its scramjet engine was aided by a Pegasus rocket launched from a Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bomber. In August 2014, a China-made hypersonic glider flew at Mach 10.

AT SUCH SPEED, CROSSING THE PAC IFIC OCEAN TAKES LESS THAN TWO HOURS

Other developments include the SpaceLiner concept by the German Aerospace Centre, designed to be propelled by 11 rockets into the mesosphere until the passenger vehicle can separate and fly independently at Mach 25. Lapcat-II by the European Space Agency aims for Mach 5, while a design by Airbus targets an altitude of at least 100,000 feet. Meanwhile, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency has begun engine tests for a hypersonic vehicle to be called Hytex.

Engineers have yet to figure out how to safely land such powerful vehicles, and are far from making them comfortable enough for grandma to enjoy a lemonade. But they appear to be on their way to proving that passenger hypersonic transport is no more just a flight of fancy.

THE AURORA PROJECT

When a trophy-winning international aircraft recognition specialist fails to identify an aircraft, conjectures fly. In the case of specialist Chris Gibson in 1989, a sighting of an isosceles triangle-shaped delta aircraft fuelled on-going rumours of ‘black’ missions and secret aviation projects by the US. In 1990, a magazine found an entry named Aurora in the 1985 US budget, which allocated $455 million for “black aircraft production”. In the following years, unusual sonic booms and contrails helped solidify the legend, as did intercepts of radio transmissions involving an aircraft seemingly flying at 67,000 feet. The US government, though, says all evidence related to the Aurora is circumstantial or pure conjecture, and denies it ever existed.